In recent decades, the growth of e-commerce exploded trade of small dollar shipments, which were waved through customs without duties, taxes, or burdensome paperwork.

Now, regulators have to apply supercharged enforcement expectations to billions of additional yearly shipments, and logistics providers have to prevent delays, manage duties, and reduce risk for hundreds of billions of dollars worth of additional parcels. Learn about the sheer scale of de minimis shipments; the illicit narcotics, transshipment activities, tariff avoidance, and consumer and market concerns that spurred policymakers and regulators to revoke exemptions; and why the end of de minimis exemplifies a new era in which the costs of expanded customs enforcement is balanced with the need to keep trade flowing.

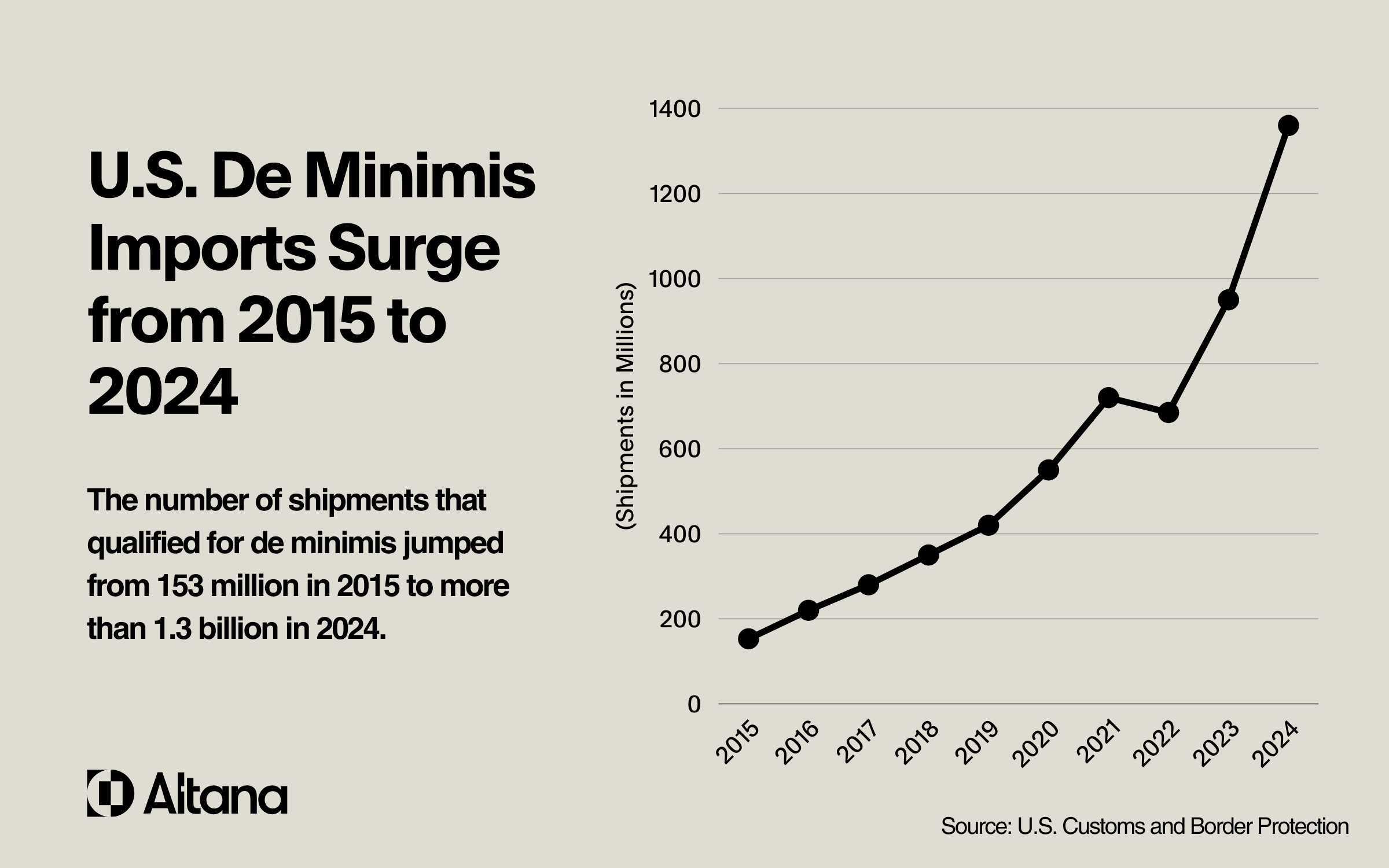

Volume of small dollar parcel shipments explodes in the 2010s and 2020s, leaving most cargo spared from full compliance and enforcement work

Leading up to 2025, imports of small dollar parcels skyrocketed, and de minimis exemptions left regulators and shippers accustomed to a trade environment in which the majority of cargo entries attracted limited enforcement.

By 2024, the more than 1.3 billion de minimis shipments accounted for 92% of all cargo entering the U.S. 60% or more were estimated to come from China. Goods imported under the Section 321 rule were not required to have goods classification, but a Congressional report suggested that many shipments of retail and apparel goods, as well as consumer electronics such as headphones, chargers, and gadgets, were granted the de minimis exemption. The upshot: Over the past decade, a vast majority of imports cleared customs without meeting anything close to current expectations for rigorous, multi-tier compliance, tariff, and enforcement work. Regulators and shippers were not operationally or financially prepared for the exploitation of small dollar trade exemptions by bad actors, or the sharp shifts in trade policy that exploitation would spark.

De minimis shipments became a route to traffic narcotics, transship goods, and side-step tariffs and consumer protections

Permitting a vast majority of imports to claim de minimis exemptions opened up avenues for narcotics trafficking, good transshipment, and avoidance of tariffs and consumer safety standards.

Counternarcotics and consumer safety

- 98% of narcotics seizures by case count

- 97% of counterfeit goods seizures — totaling over 31 million fake items

- 77% of health and safety seizures, including weapons parts and fentanyl precursors

The sheer volume of de minimis shipments — CBP processed roughly 4 million per day in 2025 — stressed regulators’ efforts to secure ports of entry and guard consumer safety.

On any given day, we could receive and process 750,000 to a million de minimis shipments. We have limited resources. We only have X number of staff. There is no physical way if I doubled or even tripled my staffing that I could manually look at a significant percentage of that. So due to the volume, it’s a very exploitable mode of entry into the U.S.

Andrew Renna, Assistant Port Director for Cargo Operations, JFK Airport

Transshipment and tariff avoidance

The changing nature of small parcels trade policy eventually turned de minimis shipments into a common avenue for illegal transshipment and tariff avoidance.

In May 2025, the de minimis exemption was repealed for shipments of Chinese origin. What ensued was systemic rerouting. Shippers added to goods’ supply chains a stop in a new country where the de minimis exemption was still in place — a move referred to as “the Tijuana two-step.” When the U.S. fully eliminated the de minimis exemption just months later, in August 2025, it was a sign that regulators would no longer pick-and-choose on enforcement of small packages based on supposed country of origin.

Market manipulation and consumer standards

Across the globe, de minimis shipments were linked to violations of product safety and unfair market competition.

The EU, in particular, saw its stringent standards around product safety and rules ensuring a competitive local market for small and medium-sized European businesses side-stepped through de minimis. The EU Commission reported that around half of the fake products seized at EU borders that infringed on intellectual property rights of European businesses were purchased online. As e-commerce is booming, we must step up efforts to prevent non-compliant products from entering the EU market and to ensure fair competition for both European and third-country operators. Our customs authorities are the first set of eyes at the border so we must equip them with the appropriate instruments to strengthen our enforcement capacities.

Maroš Šefčovič, EU Commissioner for Trade and Economic Security; Interinstitutional Relations and Transparency

The end of de minimis, and the new paradigm for trade compliance, enforcement, and facilitation

With the elimination of de minimis, customs agencies and logistics providers are now exposed to billions of dollars of enforcement and compliance costs as they classify goods, qualify free trade agreement qualification, and verify and enforce compliance with trade regulations, from forced labor to expanded tariffs. Additional costs related to the ongoing government IT overhaul necessary to process nearly 10X more shipments could slap both customs agencies and logistics providers with high costs to build and integrate into new enforcement technology. Component-level enforcement on upstream supply chain activity crystallizes the scale and complexity of new compliance and enforcement activities. Among the billions of shipments that previously qualified for de minimis are significant volumes of inexpensive consumer electronics. Section 232 investigations into critical minerals, semiconductors, and polysilicon could result in percentage-based levies applied to those raw materials within inexpensive electronics. With a large portion of trade from China subject to Section 301 national security tariffs, billions of shipments that once incurred no duties at the border now must be calculated and enforced for multiple forms of levies that may even stack upon each other.