The ongoing global trade war, like past economic conflicts, features high tariffs, stock market turbulence, and changes in how goods and products move around the world.

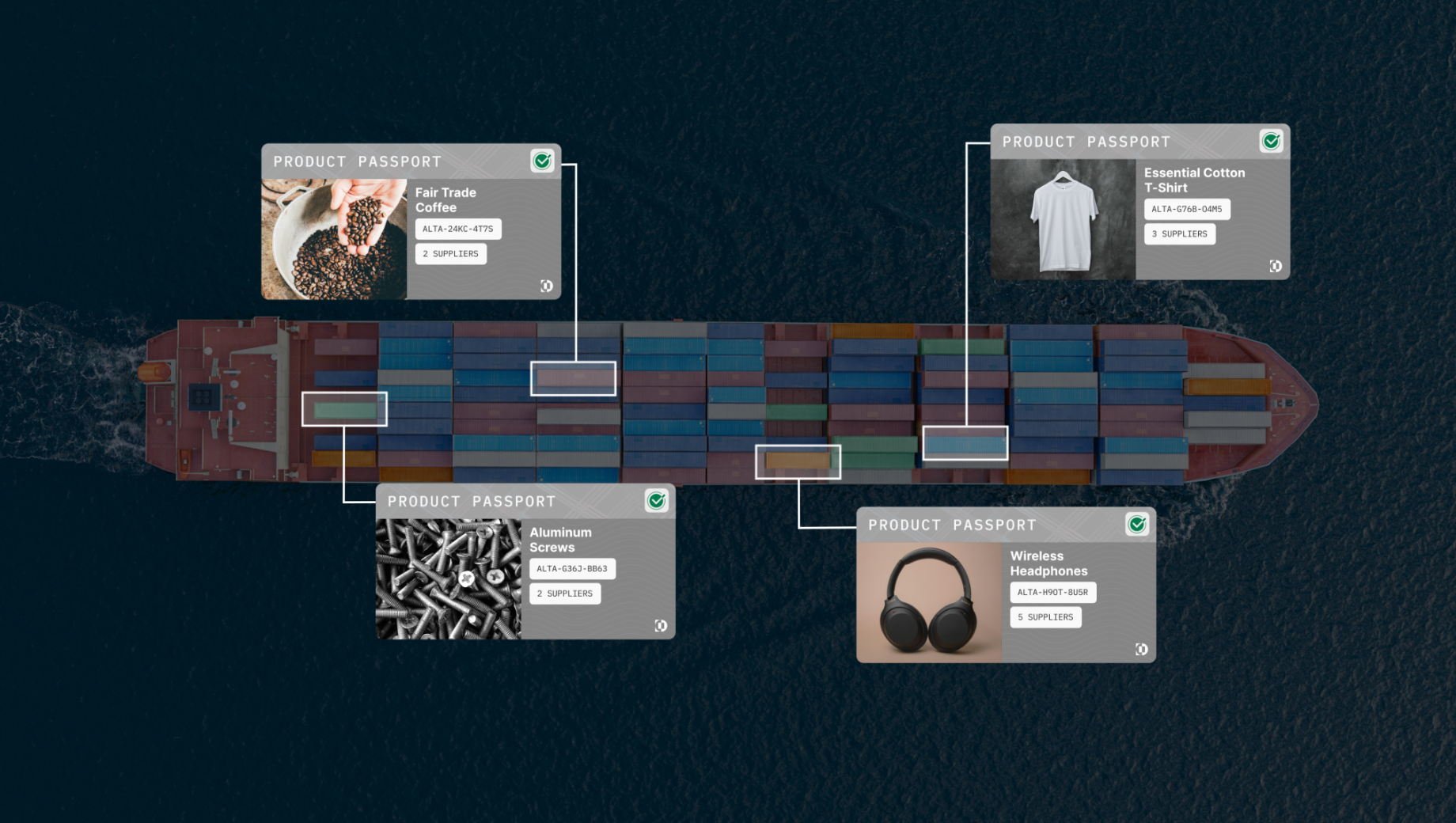

Unique to this trade war is the importance of component parts — the rubber in the shoe, aluminum in the curtain rod, cathode materials in the electric vehicle battery, critical minerals and polysilicon in the engine, laptop, or missile. Alongside extensive Chinese extraterritorial export controls on rare earths and critical minerals, heightened U.S. tariffs on these component parts introduce a trading world in which where a product is made still matters, but so does what’s inside it. Levies aren’t just placed on goods, but on the goods within the goods. The presence of certain components in products — and the percentage of raw materials like steel and aluminum they contain — are triggering costly levies and threatening qualification for free trade agreements (FTAs) like North America’s USMCA. Analysis from Altana’s product network, which is built on the world’s largest, most accurate picture of the global supply chain, indicates that component-based tariffs also skyrocket the sheer amount and value of trade that is subject to levies. Learn more about the types of component-based tariffs, and how they complicate enforcement, increase exposure to levies, and demand the ability to know and manage a product’s journey from raw material origin to finished goods.

What are component-based tariffs?

Component-based tariffs are levies applied to not just where a product is made, but also what’s inside of it. Underlying the U.S.’s component-based tariffs is an effort to create stronger barriers to trade with geopolitical rivals, especially China, by closing the friendly-nation backdoors through which Chinese goods and components enter the U.S. market at a lower price.

Component-based tariffs complicate country of origin, effectively requiring regulators and importers to know the country of origin of the parts and materials within a product in addition to the origin of the product itself to accurately enforce and calculate tariffs.

Consider major component-based tariffs, and how they tax goods upstream in U.S.-bound supply chains:

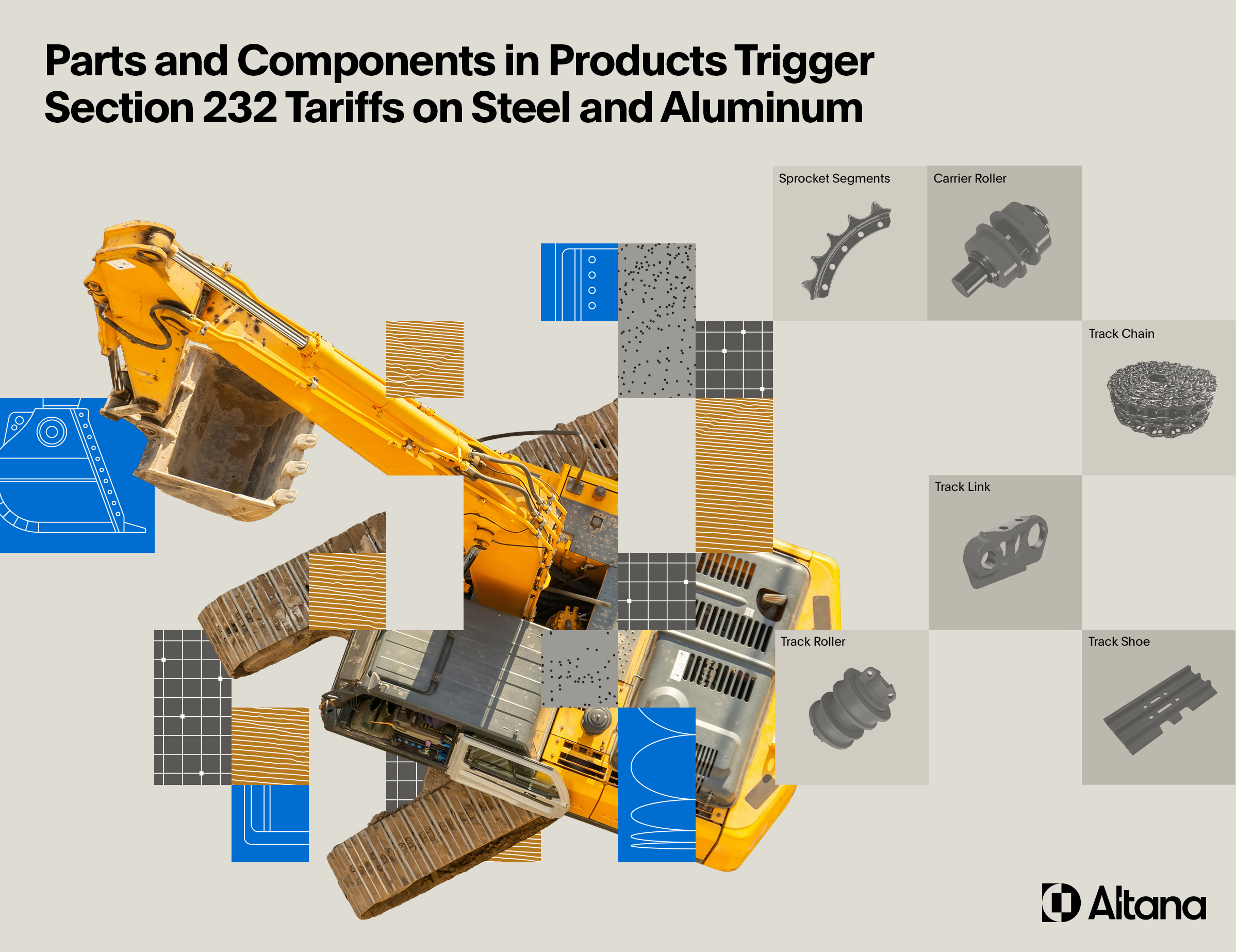

- Section 232 tariffs apply to steel, aluminum, copper, other materials, and their derivative parts. An excavator or piece of industrial equipment from Mexico or Canada that includes steel subassemblies from China may trigger a heightened levy on the percentage of Chinese steel, which won’t qualify for USMCA cost savings.

- Section 301 tariffs target Chinese-made batteries and chips. An electric vehicle chassis from South Korea includes lithium-ion battery packs containing Chinese materials. These cathodes and electrolyte salts are taxed at the heightened China trade rate.

- Anti-dumping/countervailing duty “see through” rules enable regulators such as U.S. CBP to apply anti-dumping levies against the components within products. For example, CBP can “see through” a curtain rod assembled in Cambodia with Chinese-origin aluminum extrusions, and enforce anti-dumping duties on the percentage of Chinese aluminum present.

Altana Analysis: Component-based tariffs expand breadth, complexity of existing and proposed levies

Analysis from Altana’s product network demonstrates that this trade war’s component-based tariffs multiply the amount of trade subject to duties, complicating enforcement for customs agencies and the ability to quantify and mitigate exposure for importers.

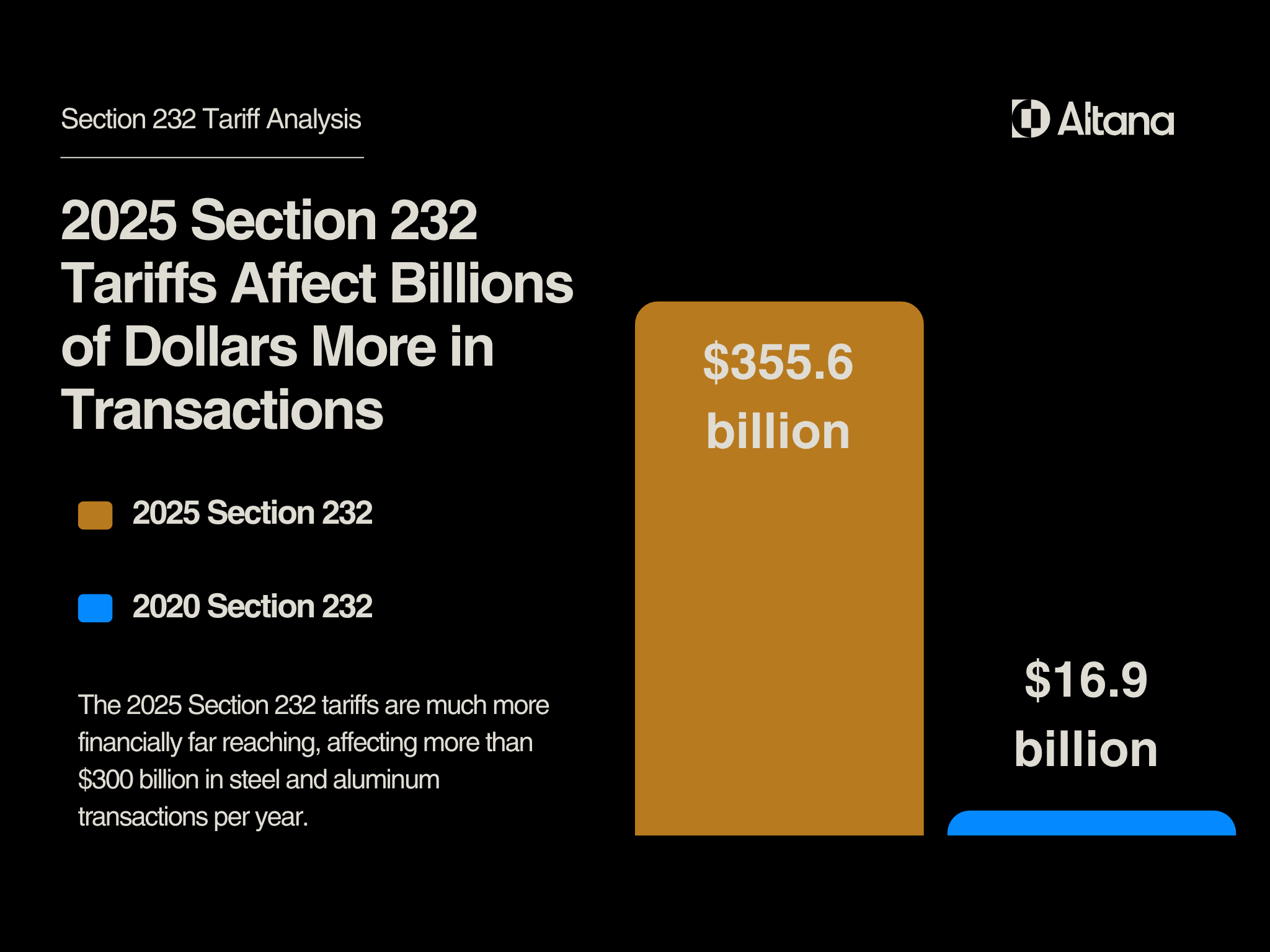

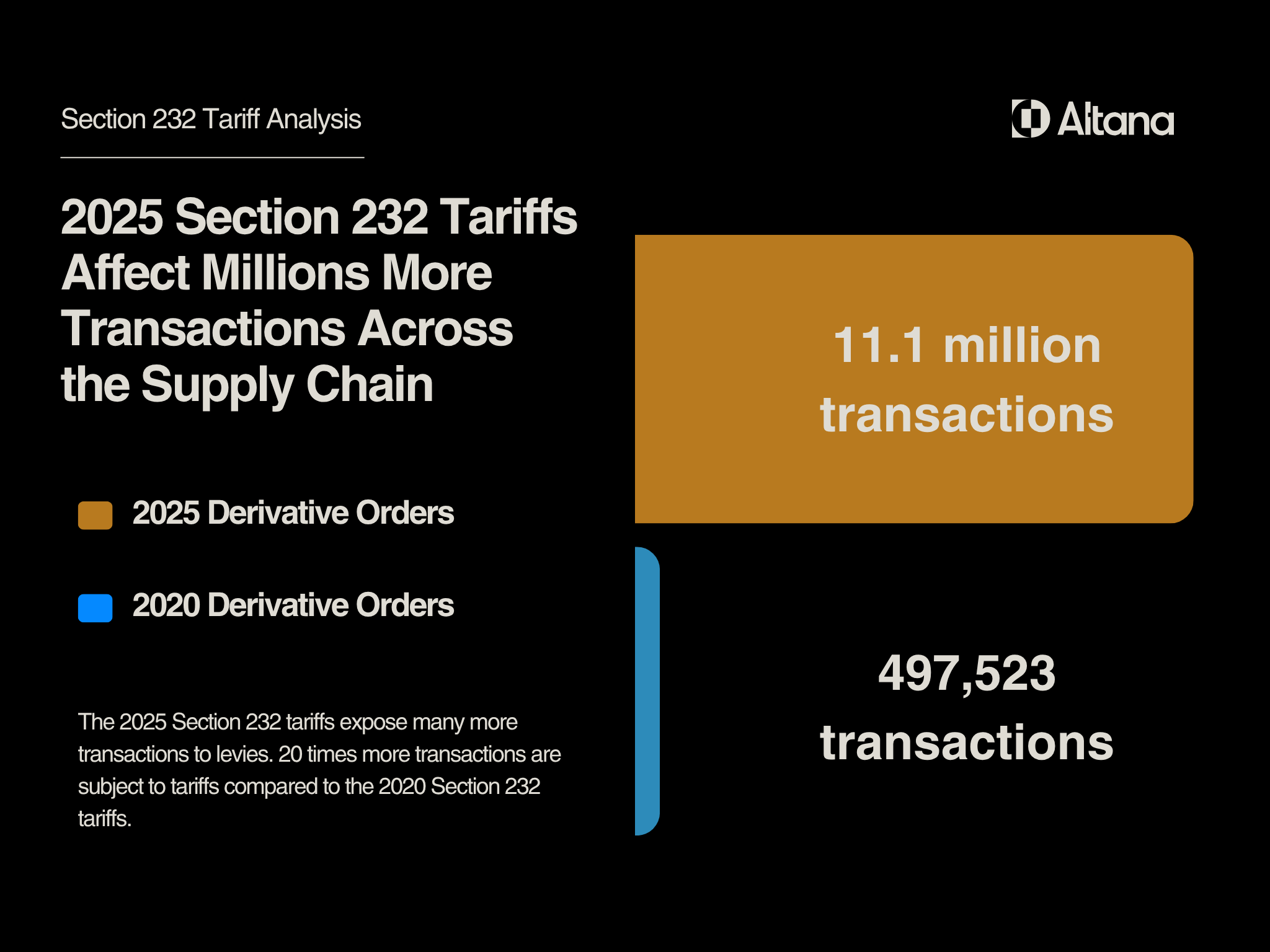

For example, expanded Section 232 tariffs on steel and aluminum in 2025 are subjecting 15 times as many companies and hundreds of billions of dollars more transactions to levies than 2020 national security tariffs on the same materials.

11 million yearly import transactions of steel and aluminum derivative articles are subject to Section 232 component-based tariffs, compared to less than 500,000 transactions for the 2020 levies, Altana’s analysis reveals. Those transactions were valued at more than $350 billion, compared to $17 billion in imports subject to the 2020 tariffs.

The analysis showed that Section 232 tariffs on steel and aluminum disproportionately affect the auto industry, the U.S.’s largest importer of aluminum products, but also hit companies in scientific manufacturing, civil engineering, mining, transportation manufacturing, hardware and plumbing, and more. Additional Section 232 tariffs on components made of wood, copper, and other materials likely introduce a similar surge in tariff exposure. And ongoing Section 232 investigations into critical minerals, semiconductors, drones, drone components, and polysilicon could lead to higher tariffs on upstream product inputs and components vital to a large swath of American supply chains.

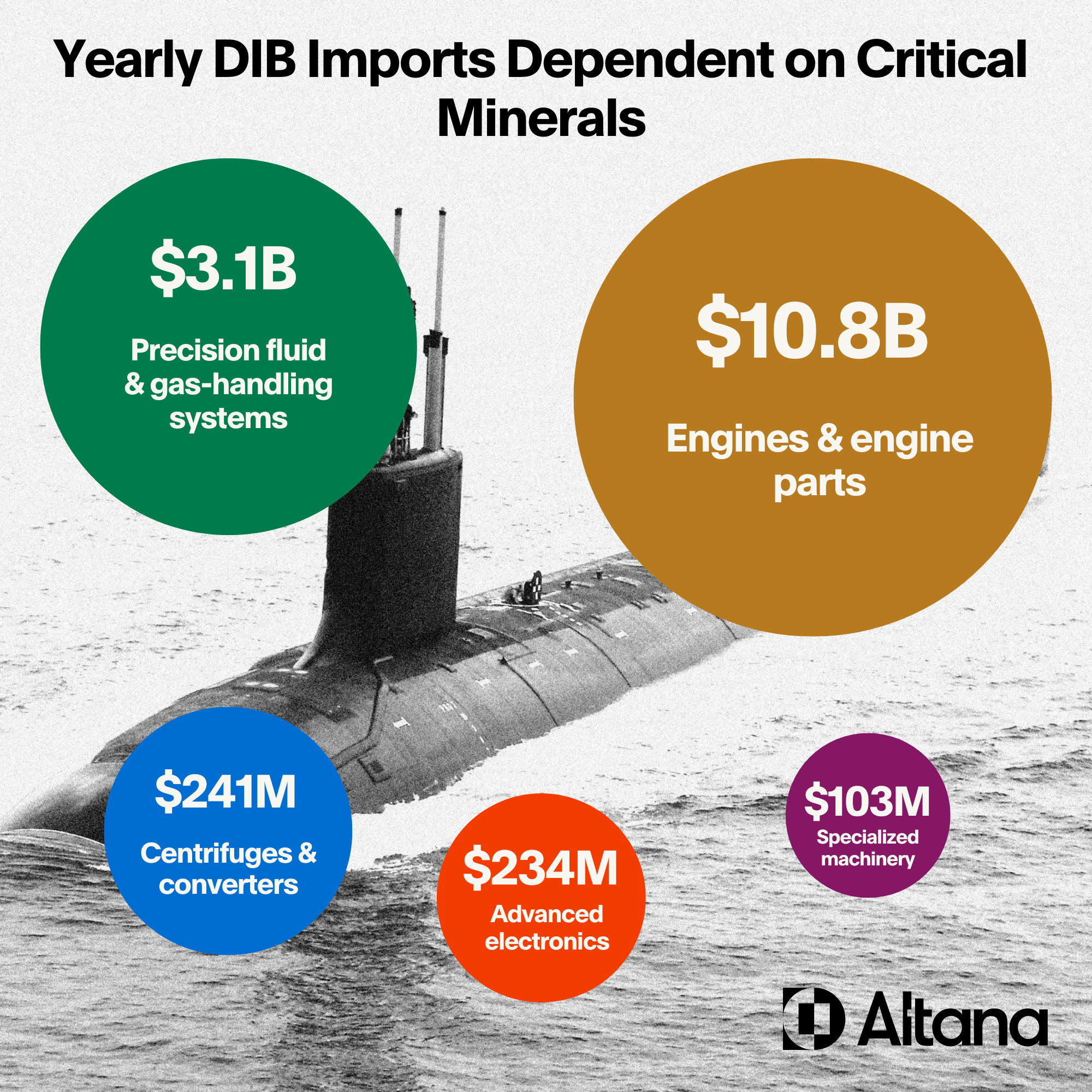

In defense alone, Altana research reveals that $14.2 billion of U.S. defense prime imports had critical minerals present upstream in the supply chain. Some of these were of finished parts such as internal combustion engines or converters; others were sub-components necessary for these applications, such as lithium-ion accumulators or heat exchange units built for extreme environments.

Played out industry-by-industry, and component-by-component, the expansion of Section 232 and other component-based tariffs complicates trade for businesses and regulators.

A larger body of trade is subject to tariffs, and the huge exposure that needs to be enforced by regulators and quantified or mitigated by importers exists upstream in product value chains, hidden and hard to trace.

Regulatory efficiency and tariff cost savings are possible with Altana. Product-level visibility and traceability give importers and regulators a common picture of products and risk factors to collaborate and communicate on tariffs, and adjust to upstream, component-based enforcement.